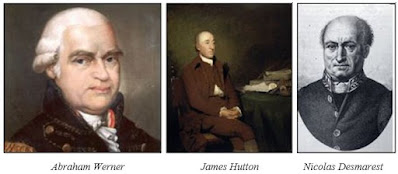

Back in 1788, Scottish polymath and geologist James Hutton, in his seminal work titled Theory of the Earth, came up with a concept in geology that came to be known as uniformitarianism.

The basic assumption in uniformitarianism is that we can interpret Earth's past history by assuming that the processes we see operating today were essentially the same processes operating in the Earth's past. This concept was later summarized by the memorable phrase "The present is the key to the past." While not always strictly true, in some ways the ancient Earth was different from the modern Earth, it is often a good guiding principle.

As an example, I took a picture in summer 2022 of a place called Duck Pond in the Mohonk Preserve on the Shawangunk Ridge near New Paltz. At the time, there was an issue with the dam impounding the pond and water levels were very low exposing the bed of the pond in places. The summer sun dessicated the mud forming mudcracks.

Here's a picture from the same month and year as the previous shot but taken in Sojourner Truth State Park in Kingston. This is a slab of 420 million year old rock (Late Silurian Rondout Formation) showing what appear to be preserved mudcracks. The concept of uniformitarianism tells us that it's reasonable to assume that this structure in the rocks are, in fact, mudcracks and formed in a similar way to those we find in the modern world.

And, importantly, these mudcracks tells us something about the paleoenvironment that existed here in Ulster County in the geologic past. It's not the whole picture, because mudcracks can form in different environments (a drying up lake bed as above or perhaps a muddy tidal flat on a shoreline) but other features in the rock, such as fossils, might help us figure that out.

Similarly, one can look at ripples in sand, like these in shallow ocean water I took at Ocracoke Island in North Carolina a few years ago.

Then we can look at 420 million year old (also Late Silurian Rondout Formation but hear High Falls, NY) rock and find preserved ripple marks.

Here's another picture of ripple marks from the Mohonk Preserve in the Shawangunks in even older rock (Mid-Ordovician Martinsburg Formation). I didn't take this picture, it's from a 2009 New York State Geological Association Field Guide (although I was on this trip).

Once again, the interpretation is that these ripple marks preserved from hundreds of millions of years ago in rocks formed by the same physical processes that form ripple marks in sand today - back and forth currents of water or wind.

These types of features are called sedimentary structures - essentially fossils of features formed in sediments and then preserved in rock as the sediments lithify. They are invaluable features for attempting to unravel the ancient geological history of an area like the Hudson Valley.